What happens when you try to combine architecture and landscape? This is the question which has underpinned our design work for several years. Perhaps the question might be better framed as ‘why?’ and for us, there’s at least three important reasons which we cover below and illustrate with case studies.

Just as a building can impact on the landscape around it, the design of landscape around a building can have a significant effect on the building. This can be put to a positive use when designing an external space.

The traditional walled kitchen garden hid the less visually appealing working areas but simultaneously created a microclimate suitable for growing fruit and vegetables by storing heat in the brickwork, providing vertical surfaces for growing fruit and sheltering the area from damaging winds. This general multi-layered approach is still valid today and is one of the main starting points for our projects.

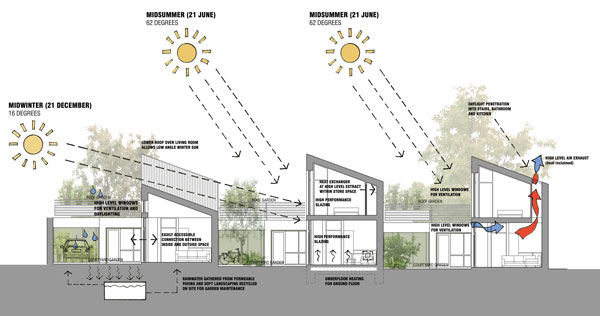

From large-scale landscape interventions, such as wind breaks on exposed farms, we know that trees can protect from prevailing winds. However, this can be taken further by locating shrubs and climbers against buildings to reduce heat loss (as well as providing beautiful fragrance) in winter and increase cooling in summer through transpiration. If you start to consider whether trees and shrubs are deciduous or evergreen, you can also plant for year-round or summer solar shading. Our ‘Hedge Home’ project includes extensive use of green walls (more of that later), climbers and planted balconies to increase connection to the outside and shelter the building fabric.

In built-up areas, the extent of hard surfaces and lack of natural permeable surfaces creates increased stored heat build-up and water run-off, sometimes contributing to flooding. Strategies we have used include specifying permeable paved surfaces, rainwater swales with resilient planting and green/biodiverse roofs to attenuate rainwater flow. Front gardens are worthy of particular attention as more and more are reduced to hard, barren parking spaces; this is likely to become even more of an issue as electric cars become more common and home charging is required. We explored this issue in our ‘Growing Home’ project, which includes ‘kitchen’ front gardens to tackle social isolation and fragrant, planted permeable driveways.

This term is an increasingly commonly seen in architecture and it’s quite a simple, useful idea, essentially connecting occupants of buildings with the natural world. The general aim is to improve health and well-being using strategies such as reducing barriers between inside and outside, or using natural materials.

How you design connections between inside and outside can be difficult when you get into the detail. For many years the answer has been to effectively seal buildings and use technology to control the environment, but that has created its own problems, increased fossil fuel energy use, sick building syndrome, etc. Our attitude is to harness the best of technology and work with the natural world to create healthy and inspiring homes and workplaces by considering how spaces are to be used and designing the local microclimate accordingly.

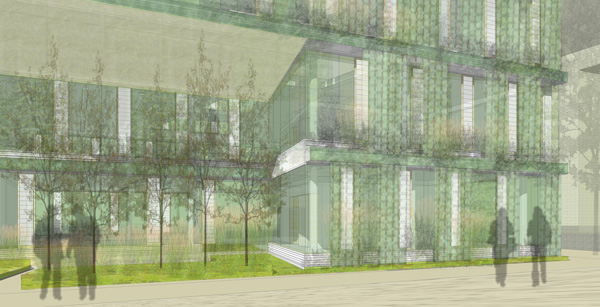

One method we have been investigating over several projects is the green wall or façade. Green walls can significantly improve local air quality by capturing and removing particles from the atmosphere and this principle can be used externally as well as internally. For instance, our prototypical 'Supergreen Workplace’ which incorporates green walls alongside openable windows to allow connection with outside whilst improving air quality and providing natural shading.

More dense green ‘living’ walls can provide solar shading, reduce over-heating in the summer, increase privacy and encourage beneficial wildlife, including pollinating insects. The orientation needs to be taken into account when specifying plants and irrigation is of course critical and we went into significant detail choosing plants which would be successful and offer year-round interest. This is also the case for the internal green walls and planting, shown to clean the air, which were also incorporated throughout the Supergreen Workplace.

We consider the specification of materials and plants for a project, understanding that they can have a long-term impact on both the enjoyment of the space and the greater environment. Where possible, we investigate what materials and planting have been successfully used locally can offer useful clues at the outset of the project. Firstly, planting using ‘right plant, right place’ principles is inherently more likely to succeed in the long term and require less maintenance and less resources. Choosing locally sourced, low-embodied energy products can also help to reduce the carbon footprint of the project.

During the design process and when building, reducing the amount of material taken off site and taken to landfill is considered. If space allows, re-use of material on site can create useful changes of levels or landscape features for environmental control or habitats such as wildlife areas. Elements such as bricks and paving can be broken down to be used as aggregate on green roofs or creatively reclaimed for walling. We specify low-energy/low maintenance products such as solar or low energy LED lighting and fountains as a matter of course. Products made of recycled materials are worth investigating, but they may not suit every project. We tend to look into specifying reclaimed materials where it is feasible such as bricks, paving and tiles; the bonus with these products is that they can offer an interesting patina or bring an extra textural quality to a project.

This is a large, evolving subject with lots of on-going research, but essentially designing sustainably, considering the microclimate and its relationship to the greater environment doesn’t have to be a change of approach, in fact it can support and strengthen your design decisions.

The project is composed of five linear blocks, four carved out from the existing building to form a series of naturally lit ‘making’ environments, each separated by a landscaped courtyard, which can be used as an extension of each workshop and allows daylight to penetrate deep into the plan. The primary structure, including the roof, front and rear walls of the existing building are retained.

The ‘making’ blocks are connected by a perpendicular double-height and full-length gallery/circulation zone, tying the existing wall to the new insertions. The steel-framed glazed vierendeel truss rests on and peers over the existing wall’s structure, accommodating the mezzanine level and associated conference spaces.

The Maker-In-Residence Units are linked by a linear courtyard space taking its cue from the ‘making’ courtyards, allowing an external making space and an external gallery/street, connected back directly to the Reception/Lobby zone. The Administration and Lab spaces at Second Floor level have views over the garden roofs, connecting back via bridges to the existing green spaces to the rear of the site on the hillside.

The courtyard housing model allows the creation of private houses and courtyard gardens through consideration of site layout and orientation, whilst creating open views to communal external spaces and beyond the site perimeters. Houses and courtyards are precisely arranged to maximise sunlight for passive solar heating over the low pitched roofs of adjoining houses.

The model for high density courtyard housing is similar to the Kingo and Fredensborg housing designed by architect Jorn Utzon in Denmark in the 1950s. These housing projects designed around enclosed private courtyards allow residents to use this for any purpose, as messy or neat as they wish, and yet still preserve an ordered communal public face. These exemplar housing schemes influenced a number of British examples such as the grouped housing designs of Aldington and Craig (especially Turn End at Haddenham, Aylesbury) and the heavily landscaped Span housing estates, which show how such strategies can be successful and popular in this country.

The courtyard gardens are configured as extensions of the ground floor living areas. Access to the living room, dining room, kitchen and bedroom through sliding doors direct to outside allows the functions of the house to extend naturally into the garden. There is no restriction on the design or use of the courtyard gardens (other than the size provided).

While the benefits of green roofs are widely appreciated, the added benefits of green facades are generally less understood. As well as further reducing urban heat island effect, providing reduced rainwater discharge and increasing biodiversity, green facades can significantly improve air quality which is very important for a successful natural ventilation strategy.

Plants can result in significant local reductions in the concentration of airborne particulate matter both when the plants are internal and when external on green facades. There is extensive research into the use of plants to improve indoor air quality and maintain a healthy indoor eco-system but recent studies have also shown how use of green facades can result in significant local reductions in external concentrations of particulate matter as the leaf surfaces of plants capture and remove particles from the atmosphere.

Green facades are most effective when planted over the whole height of the building using planting with a high density of leaves. Vegetation on the lower storeys is effective in removing locally generated pollution eg from traffic and can clean air prior to it entering the building. High level façade planting is most effective at removing wind driven pollution generated from further away and helps combat the ‘street canyon’ concentrating effect which can be exacerbated by tree canopies. Whilst an individual building can only improve a local area by a limited amount, if 60% of a street’s facade are planted the general air quality could be improved by 20%.

Hedge Home is wrapped in its own garden, with planted green roofs and walls. Individually the house sits on its site like a clipped topiary bush; in association with neighbouring houses, it forms a giant hedgerow. Within its living green carapace, Hedge Home comprises a flexible, informal family home with four double bedrooms over three floors. Hedge Home has direct connections to usable external spaces from every room at all floors, using these for environmental control, biodiversity, health and social contact, connecting the homeowner outwards towards the surrounding community.

Hedge Home is designed to optimise daylight and sunshine into all main rooms, gardens and roof terraces throughout the year over the roofs of the adjacent homes, maximising the effect of passive solar gain even in the winter months. The use of a stepped site arrangement enables an optimal orientation for each house no matter what angle the roads are needing to be laid out.

The living walls comprise gridded frames with planting trays allowing plants to climb on the walls. The plants chosen will relate to the orientation of each house. The living walls provide solar shading, reduce overheating in the summer, increase privacy and encourage beneficial wildlife, including pollinating insects. As well as accessible terraces, there are fully planted roof areas designed as intensive bio-diverse garden areas plus a low maintenance brown roof to the upper roof between the solar panels. Along with permeably paved driveway and path, the green roofs slow down rainfall runoff, reducing the pressure on drains. Through careful integration of suitable planting there is beneficial impact of vegetation upon the performance of building fabric. Aerial cooling through shading and evapotranspiration counteracts ‘urban heat island’ effect and acts as insulation in the winter by reducing air movement over building fabric.

RHS Greening Grey Britain campaign

Biophilic Design introduction and overview

Green roofs overview

Larger scale strategic thinking on green cities